Nearly a decade after 43 students went missing in Mexico, families are still searching for answers. During a drug war that has infiltrated every level of society and led to the disappearances of 110,000 people, can they ever find the truth?

“It’s not like when a person dies and you say, well, at least I know where they are,” says Luz María Telumbre about her only son, Christian.

She and her husband Clemente were given a two-gram fragment of bone from his right foot in 2020, six years after he disappeared. It was seemingly all that remained of him, but Christian’s family have not given up hope that they will one day be reunited.

“While I don’t have a whole body, my struggle continues,” Clemente tells the BBC documentary Disappeared: Mexico’s Missing 43.

On the evening of 26 September 2014, Christian was part of a group of male students from poor rural areas who were travelling from the Ayotzinapa teacher training college, which has a strong history of activism, to an annual protest in Mexico City.

More than 60 students gathered in the city of Iguala and took over buses at the station, asking the drivers to divert their destination – a tacitly accepted tradition in these parts of Mexico, where public transport is scarce. But as they left, they saw roadblocks had been set up and shots were fired.

Police surrounded the buses and, in the chaotic scenes that followed, 43 students disappeared.

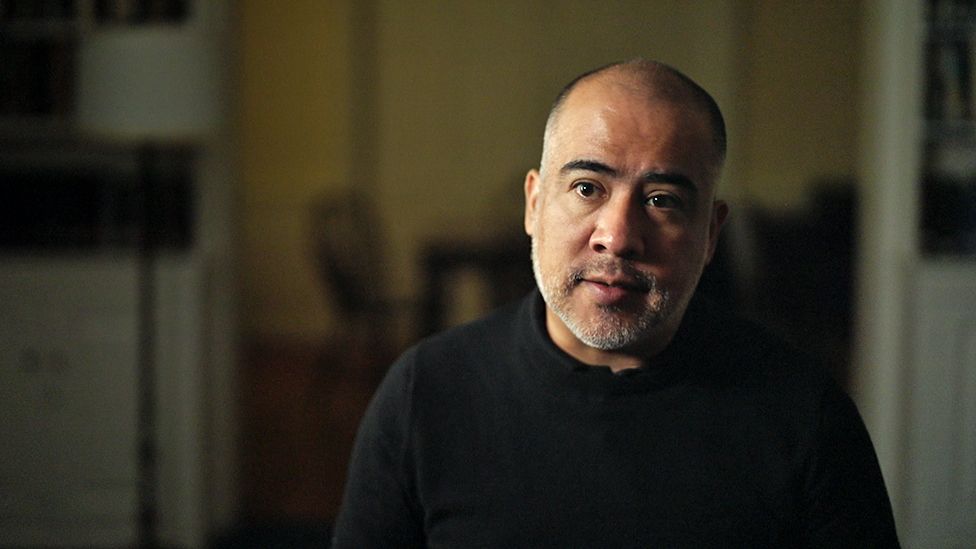

In 2019, after years had passed without finding the students or bringing anyone to justice, human rights lawyer Omar Gómez Trejo was appointed to lead a new investigation.

Now living in Washington DC because he fears Mexico is no longer safe for him, he tells the BBC: “We needed to work on the disappearance, but we also needed to work on the cover-up.”

The previous investigation, led by Mexico’s attorney general and the chief of the Criminal Investigation Agency, Tomás Zerón, had produced its answer within three months of the disappearances. The investigators declared it “the historical truth”.

They claimed that corrupt police working for the former Iguala city mayor and a local drug cartel, the Guerreros Unidos, had detained the students. Cartel members then murdered them, burned their bodies in a local dump and threw the ashes in the San Juan river.

Families of the missing were incensed that the investigators could present the case as solved without finding their loved ones. Cristina Bautista Salvador, mother of Benjamín, one of the missing students, tells the BBC the government thought its announcement would “shut them up” and “send the peasants away”.

But soon cracks began to appear in this “historical truth”. Independent forensic anthropology experts, brought in by the lawyers representing the families, cast doubt on the discovery of a bone with DNA that tested as a match for one of the missing students.

The Mexican government said the students had been on four buses when they were attacked – but CCTV evidence revealed students on a fifth bus that had never been mentioned.

Fresh hope for the families of the missing arrived when a new Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, was elected in 2018. The following year, he announced a new investigation, to be led by Mr Gómez Trejo.

“It has been the most important job I have ever had in my professional career,” Mr Gómez Trejo tells the BBC. Soon after he began work, a video of the former investigator, Mr Zerón, was leaked.

It shows a blindfolded man with his hands tied behind his back. “The first time you bullshit me, I’ll kill you, man,” Mr Zerón tells him.

Mr Gómez Trejo’s team discovered more than 60 videos of unlawful interrogations carried out during the original government investigation, led by Mr Zerón.

The suspect in the leaked video has no defence lawyer with him and is being “held captive, handcuffed”, Mr Gómez Trejo points out. “This is a scene of torture,” he says. “To torture someone is to ruin an investigation.”

With this and other evidence, Mr Zerón was accused of torture, forced disappearance and obstruction of justice. But before he could be arrested, he fled to Israel, which has no extradition treaty with Mexico.

The BBC found him in Tel Aviv, where he denied torture. “It’s probably something that I shouldn’t have said, it was out of line. You can see I threatened him,” Mr Zerón says. “But I never tortured him.”

He says he did not receive instructions to cover up anything done by federal forces and was not responsible for the students’ disappearance. Mr Zerón says he was “important enough to be blamed but not so important anyone would come to my defence”.

After the discovery of unlawful practices in the original investigation, former suspects were released from prison and began to reveal information to Mr Gómez Trejo’s new inquiry.

That led Mr Gómez Trejo to a new search site, about 1km (0.6 miles) from the rubbish dump where the original investigation claimed the bodies had been burned. In a criminal investigation, says the special prosecutor, “every millimetre, every centimetre” matters.

At the new search location, called the Butcher’s Ravine, they uncovered remains that could be traced to two more students – one of them named as Christian Rodríguez Telumbre.

Mr Gómez Trejo told a press conference in 2020 that the fact these remains were not found in either of the places identified by the first investigation – the dump or the San Juan river – meant “the ‘historical truth’ is over”.

Meanwhile, the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had been watching the Guerreros Unidos drug cartel since 2013, the year before the students disappeared.

Former DEA special agent Mark Giuffre tells the BBC the cartel, described merely as a local gang by the Mexican government, had been smuggling heroin worth about $122m a year into the US via Chicago – “an absolutely unprecedented amount of heroin coming in the United States by a single organisation”.

Surveillance showed that the cartel was using buses leaving from the Iguala station to smuggle their drugs. “It seemed to us that it was clear as could be – that the students unknowingly hijacked the wrong bus,” says Mr Giuffre.

In 2022, Mr Gómez Trejo’s investigation was given access to the DEA’s tapped telephone calls and investigative case file on the Guerreros Unidos. The phone calls “talk about the corruption existing between certain authorities and the Guerreros Unidos cartel – payments, having parties, jobs they’ve done together,” Mr Gómez Trejo says.

“What you have is the participation of federal authorities such as the army, working hand in hand with criminal groups. The proof we had was convincing and strong.”

The investigation had already raised questions about the role of the military. It was operating the camera surveillance system in Iguala on the night of the disappearance. Investigators also say the army was monitoring communications of the Guerreros Unidos cartel in real time.

But if the army was aware of cartel operations before, during and after the attacks, why did it not intervene to rescue the students?

The government had even revealed that the army had planted undercover agents in the teacher training college to spy on the students.

Investigators say that despite an order from the Mexican president to hand over all their information, the army has not complied.

“What we have received is a refusal, a lack of collaboration and obstruction in the search for the truth,” says Carlos Beristain, part of an international group of independent experts (known as GIEI) who had been investigating since 2014 and worked alongside Mr Gómez Trejo’s inquiry.

The army says it has handed over all the information in its archives and President López Obrador has said: “If progress has been made, it’s precisely because of the co-operation of the army and navy.”

On the night of the disappearance, investigators say there are moment-by-moment reports from the army, except between 21:15 and 22:30 local time. Mr Gómez Trejo told the BBC this blank space is “part of the disappearance” and “a result of erasing all the evidence, leaving no trace of what was done to disappear the 43 students”.

Armed with the telephone tap evidence, in August last year the investigation team obtained arrest warrants for the former attorney general – who conducted the first investigation with Mr Zerón – and 83 others, including 20 soldiers on duty in Iguala on the night of the disappearances.

But days later, 21 of the warrants were withdrawn by the office of the current attorney general, including most of those for the soldiers.

Mr Gómez Trejo says he was told by the attorney general he could no longer investigate the case. He decided to resign. “The rules of the game, the rules by which I came to the prosecutor’s office, have changed,” the special prosecutor says.

Mexico, 2014. Forty-three students were violently attacked, then vanished. Someone, somewhere knows the truth. Searching for answers amid corruption, cartels and conspiracies.

He fled to the US, fearing for his safety and facing a criminal investigation for his handling of the case. “They told me ‘Hey, you overdid it regarding the number of military personnel’,” he says. “It has that kind of stench, to criminalise, to undermine, to shoot the messenger.”

Mr Gómez Trejo says 16 of the arrest warrants were reissued earlier this year, under pressure from the families and the GIEI group. There are now more than 100 people in custody, including two army generals, 12 soldiers and a navy officer. The former attorney general remains in custody and denies the charges against him.

The former Iguala mayor, accused in the first investigation, is in prison for other offences. He was cleared of some charges relating to the disappearance of the students but the government says he is still under investigation.

Nearly a decade on, however, there has not been a single conviction for crimes committed against the missing 43 students.

On the 28th birthday of her son Benjamín, Cristina promises him: “I will keep looking for you until the last beat of my heart.”

The investigation still remains open, Mr Gómez Trejo says. But while the full truth about the missing students of Ayotzinapa may never be known, Mexico’s organised crime violence continues to claim more victims.

Forensic anthropologist Mercedes Doretti, who worked for the families of the students, tells the BBC that across Mexico, with limited state support, relatives of the missing are out searching for their loved ones’ remains with shovels and picks.

More than 110,000 people have now disappeared in the country’s drug war, and the number continues to rise.

“From where do we start to change the country? The ringleaders don’t get caught,” says Luz María, Christian’s mother.

“They are untouchable. This system cannot be changed, it cannot be changed. And if you meddle, they kill you.”

Source : BBC