The city once known for its resplendent culture of mushairas and poets would be reduced to one strewn with bodies of the dead. From a royal capital, its status was relegated to that of a provincial town. The city recovered itself only after 1911 and more so after Independence.

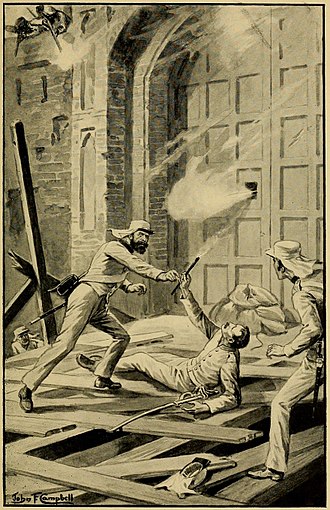

September 1857 can well be recalled as the end of an era in Delhi. The flickering flame of the Mughal empire and culture in the city had been snuffed out. After nearly five months of a frenetic rebellion by Indian sepoys, the British troops finally managed to advance into the city through the gutted ruins of their own bungalows in Civil Lines, and on the morning of September 11 they made the final assault on Kashmiri Gate. The biggest resistance took place here. As it coincided with a solar eclipse, many of the more superstitious Hindu sepoys among the mutineers stayed in and took it as a sign of the end of the conflict. With no opposition in sight, the British soldiers walked in with ease and thereafter took over the Mughal capital and changed the course of its history forever. Delhi had fallen and was declared captured on September 21.

In the days and months to come, the face of the city would change remarkably. The city once known for its resplendent culture of mushairas and poets would be reduced to one strewn with bodies of the dead and later remodelled and anglicised in a way that became unrecognisable. “From a city of culture and patronage, Delhi became a quiet city. Its status was relegated to a minor place, from which it recovered only after 1911 when the capital shifted and more so after Independence when it became the preeminent city in India,” says poet and writer Mahmood Farooqui who has authored the book, Besieged: Voices from Delhi 1857.

‘The city of the Dead’

Marching through the streets of Delhi on the morning of September 24, 1857, field marshal Lord Roberts was shaken by the horrifying sight and odour all around him caused by the four days of dreadful carnage carried out by the British army. In his memoir, Roberts wrote of the scene in the most pitiable words: “The sights we encountered were horrible and sickening to the last degree. Here a dog gnawed at an uncovered limb, there a vulture, disturbed by our approach from its loathsome meals, but too completely gorged to fly, fluttered away to a safer distance. In many instances the positions of the bodies were appallingly life-like. Some lay with their arms uplifted as if beckoning, and indeed, the whole scene was weird and terrible beyond description.”

“Dead bodies were strewn about in all directions, in every attitude that the death struggle had caused them to assume, in every stage of decomposition,” he continued.

After capturing the city, the first impulse of the British officers commanding the various units was to demolish the entire city. The destruction of Delhi was to be the punishment for the mutiny. What followed though was a full scale massacre of the residents of the city. In a recent podcast by historians William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, the former notes that the British committed its worst war crimes ever after the 1857 revolt.

Men, women, children, old and young, sick and wounded, were all put to the sword and shot for about a month. Simultaneously, orders were issued to the citizens to evacuate the city. Some managed to pass by unharmed, but not all, and whoever caught the suspicion of the British was picked out to be shot or hanged on the gallows. N K Nigam in his book, ‘Delhi in 1857’ published in 1957, notes how in Chandni Chowk “gallows were erected along this route and people were hanged in dozens at a time.” The white soldiers, along with the Sikhs, Gorkhas and the Qabalis who fought for them, roamed around the city, entering galis, kuchas and houses and putting to death almost every able-bodied man they came across. Then there were those who were tortured by flaying or red hot branding.

A sub-inspector in a suburb of Delhi, Moinuddin Khan, in his memoir narrated how thousands of women who had never come out of purdah died by suicide. When, for instance, the house of Mohammad Ali, the nephew of the Raja of Dadri was ransacked, the ladies of the house and a wet nurse with a child plunged into the well.

In their pillage of the city, the British refused to show mercy even to those among Indians who had collaborated with them and assisted them in the siege of Delhi. Historian William Dalrymple in his book, The Last Mughal (2006) notes that as per General Wilson’s orders no protection tickets would be recognised until countersigned by him, as a consequence of which very few people obtained any protection for their property.

Dalrymple in his book writes about the ordeal faced by Master Ramachandra, pro-British loyalist and Christian convert who was formerly lecturer of Mathematics in Delhi College. “Returning to Delhi after the fall of the city, he expected to be welcomed home by his fellow Christians, but instead found himself living in fear of his life just as he had done during the uprising- but while before he had been targeted on account of his faith, now he suffered mainly on account of his skin colour,” writes Dalrymple. Despite his repeated explanations of being a government servant and a Christian he was attacked mercilessly both on the streets and in his house.

Perhaps no other community suffered the wrath of the British more than the Muslims of Delhi, thereby bringing about a significant demographic and cultural shift in the city. It is important to remember the nature of the relationship that Delhi had shared with Muslims over centuries. Having experienced a long history of rule by Muslim emperors, the city was largely built with an ethos that was heavily influenced by a Persianate and Mughal culture. This intimate bond with the Muslims was to break following the revolt of 1857, as the rebels fought under the banner of a Mughal emperor.

“Muslims were not allowed to return to the city for the next three years. Many of them found refuge in cities like Rampur, Hyderabad, Lucknow and the like,” explains Farooqui. “Their property was confiscated and so was the Jama Masjid, which was returned to them only in 1861,” he adds.

Mirza Ghalib was one among the very few Muslims remaining in the city, mainly by a stroke of luck. The street on which he lived contained the houses of the hakim and courtiers of the Maharaja of Patiala who had sent troops and supplies to the British during the revolt. In return, the British had provided his neighbourhood with protection. The poet’s writings of the time give an account of the intense loneliness experienced by him in a city and at a time when there was no one around him with whom he could share his tastes and art. “By his own estimate there were barely a thousand Muslims left in the city; many of his best friends and rivals were dead; while the others were scattered in ditches and mud huts in the surrounding countryside,” writes Dalrymple. He cites a verse in a letter that Ghalib wrote to a friend in Rampur describing the sorry fate of the Muslims of Delhi:

“Every armed British soldier

Can do whatever he wants

Just going from home to market

Makes one’s heart turn to water.

The Chowk is a slaughter ground

And homes are prisons.

Every grain of dust in Delhi

Thirsts for Muslims’ blood.

Even if we were together

We could only weep over our lives.”

An altered landscape and culture in the city

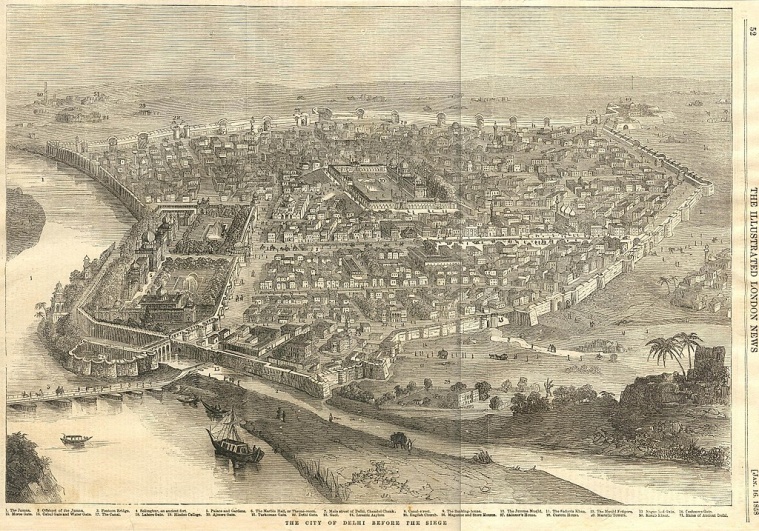

As the residents were being driven out or killed, the physical form of the city too was altered by the British. The original plan was to demolish the entire city including the Red Fort and Jama Masjid. But later the governor-general decided on pulling down only the built up defences and edifices close to the fort. Historical buildings and places of worship were decided to be kept intact. The British accommodated their troops inside the fort, while all houses and other buildings in the vicinity around a radius of 440 yards were completely levelled to the ground. “This was done so that in case of another rebellion, the British could have a clear canon shot from the Red Fort to the Jama Masjid,” says Farooqui.

“The level ground towards Darya Ganj which once had beautiful buildings and the famous dargah of a Muslim saint and the Akbarabadi mosque as also the frontage of the Urdu Bazar at the site where Edward Park stands, were razed to the road level,” writes Nigam. He adds that during the excavations of the Parade Ground in 1921-23, beautiful houses built of marble and other stones were discovered beneath the ground.

The Jama Masjid, Fatehpuri Masjid and Kalan Masjid were also occupied by British troops for a while before being restored to Muslims in the 1860s and 70s. The Fatehpuri Masjid was sold to Lala Chunna Mal, a wealthy textile merchant who won the favour of the British after the revolt.

No longer was Delhi a royal capital. Its status had been reduced to that of a provincial town, part of the Punjab province. Between 1857 and 1861, Delhi was managed by the British army. When returned to the civilians, the administrative vacuum left by the army was filled by the setting up of a municipality, a Jama Masjid Committee and a Delhi Society. Historian Narayani Gupta in her book, Delhi between two empires, 1803-1901: Society, government and urban growth (1981) writes that the British officials used the municipality to encourage their loyalists.

The British rewarded their loyalists with wealth, land, titles and positions of honour. “As soon as any of them died (in some cases even in their lifetime) their heirs were granted marks of recognition. Hence the phenomenon of teenagers becoming members of the municipality and being noticed in the gazeteer lists,” writes Gupta. The majority of these beneficiaries were Jain and Hindu bankers and mercantile families.

“By the time the exiled Muslims of the city managed to come back, their role and position got diminished and a new rich trading community which had supported the British had come up,” explains author Rana Safvi who has recently translated the book, Tears of the begums: Stories of survivors of the uprising of 1857 (2022). “The traders like Chunna Mal were now flourishing while the nobility which was once a symbol of culture, and had patronised mushairas, poetry disappeared completely or lived in very diminished circumstances .”

Safvi notes the example of Zahir Delhvi, an official in the court of Bahadur Shah Zafar and an accomplished poet who had to leave after the revolt and he came back in 1864 only to find his house confiscated and like many other survivors of his class had to leave for the states of Alwar and Jaipur for employment. Then there was Imam Baksh Sehbai, a professor of Persian and Arabic in the Delhi College. He along with 1,400 others were killed in Kucha Chelan when the British attacked there. Mir Panja Kash, the leading calligrapher in the Mughal court was also killed by the British army while he was defending his home.

Gupta in her book notes that with the Muslims now attenuated, the rivalry between Hindus and Jains, and particularly their respective leaders, Lala Rammi Mal and Lala Mahesh Das, both very rich bankers, became prominent.

Historian Swapna Lidddle explains that much of what happened after 1857 needs to be seen in context of the half a century of change already brought about by the British after the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803. “The Mughals were of course there in the Red Fort, but the East India Company was the real ruler of Delhi and it had already brought about a lot of cultural changes,” she says.

The first western styled college, the Delhi College, was established in 1825 which promoted a new kind of education. Another important development was the use of print technology, which was being used in very creative ways. “It democratised the literary space,” says Liddle. She explains that the print space was developing a culture of civil society. There were also some new institutions that had been established by the British before revolt, such as the Archaeological Society of Delhi and the Vernacular Translation society.

“Apart from removing the Mughal emperor, what 1857 did was it led to the destruction of some of the most important and rich people who were patrons of poetry and education and were very involved in these institutions,” says Liddle. She explains that even in the institutions established by the British, the leading roles were being played by Indians. One of the main contributors to the archaeological society, for instance, was Ziauddin Ahmad Khan from the Loharu family. “These institutions were a meeting ground for Indians and Europeans. 1857 fractured that relationship and put an end to the institutions as well,” Liddle says. Some of these intellectual activities were renewed with the establishment of the Lawrence Institute in 1863, the St. Stephens College in 1881, and the Hindu College in 1889.

The post-revolt decades of the 1860s and 70s were also the time when much of the public works in Delhi was established by the British. “The first public works stemmed as much from considerations of military exigency as commercial and civil administrative needs,” writes Gupta. The railway line for instance, was built through the city rather than outside because it made for greater security in the case of another uprising.

New roads were built through the most densely populated parts of the city, much to the distress of the local inhabitants. Gupta in her book writes about how the 100-feet-wide Queen’s Road and Hamilton Road built as adjuncts to the railway line displaced hundreds of people. In 1865, a general hospital was established in Chandni Chowk to replace the dispensary that existed there before 1857, and in 1867 the Sadar Bazar was inaugurated to formalise the shops that had sprung up to cater to the needs of the army.

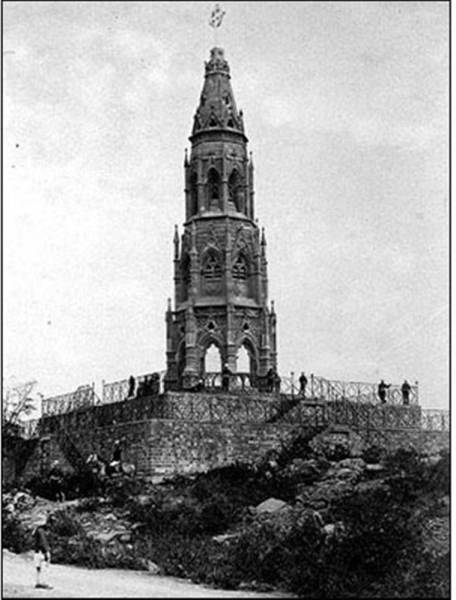

The primary objective of the British in the period after 1857 was to wipe out the memory of the Mughals from Delhi. Thereafter begins a conscious commemoration of British sites of valour. Perhaps the most striking example of this was the four tiered gothic style monument, the Mutiny Memorial built by the British government on the Ridge where it continues to stand today. It listed out with statistics those who were killed in the revolt. It was only 25 years after the Independence of India that the government renamed this monument as Ajitgarh (place of the unvanquished) and erected a plaque, stating that the ‘enemy’ mentioned on the memorial were “immoral martyrs of Indian freedom.”

Source : The Indian Express