“We’ve been fighting for more than 10 years to get the truth about what happened to my father acknowledged,” says Rosa María Payá.

Ms Payá, 34, never had any doubt that the car crash which killed Cuban dissident Oswaldo Payá and fellow activist Harold Cepero in 2012 was no accident.

“The Cuban regime killed my father and Harold Cepero,” she told the BBC after the release this week of a new report – issued by the leading regional human rights entity for the Americas – which concludes that Cuban state agents “participated” in their deaths.

Oswaldo Payá was one of Cuba’s main pro-democracy campaigners, who spent decades pressing for human rights and democracy on the Communist-run island, where political opposition is banned by law and actively persecuted.

Cuban authorities have long insisted that the death of Oswaldo Payá, denounced by state media as an allegedly CIA-backed “well-known counterrevolutionary leader”, was an accident. State media commentators have also attacked his daughter as a “liar”.

In 1988, Oswaldo Payá founded what became one of Cuba’s largest opposition groups, the Christian Liberation Movement.

He also created the Varela Project, a campaign aimed at gathering the 10,000 signatures needed under the Cuban constitution to petition the National Assembly for a referendum.

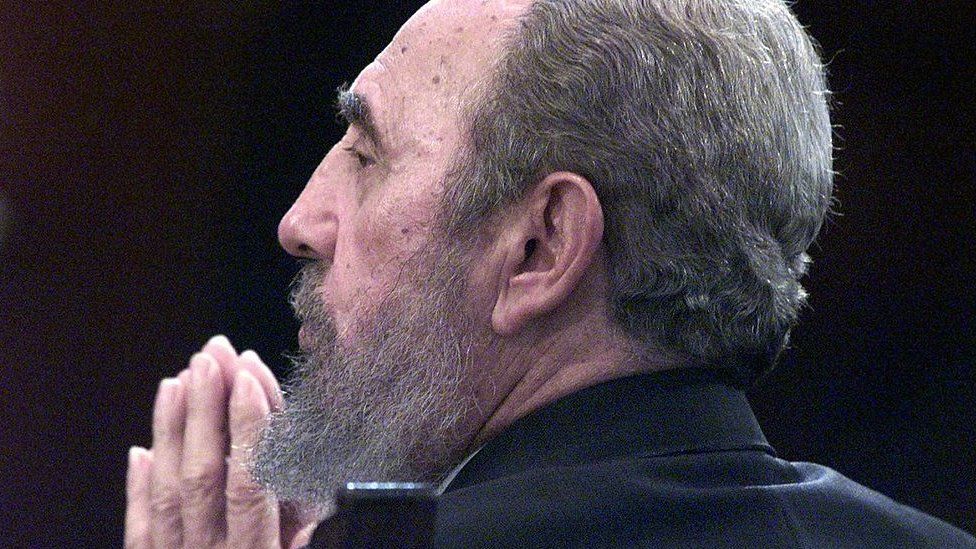

His plan was to bring about change in Cuba, which had been led by Fidel Castro since 1959, from the bottom up.

In the referendum, Cubans would have been asked if they backed changes to the law to guarantee freedom of expression and association, free and fair elections, and an amnesty for political prisoners.

Payá and his fellow activists went door to door asking for support and, in May 2002, they carried cardboard boxes bearing the signatures of 11,020 Cubans to the National Assembly.

But even though it had met the target, the Varela Project was not widely known at this point.

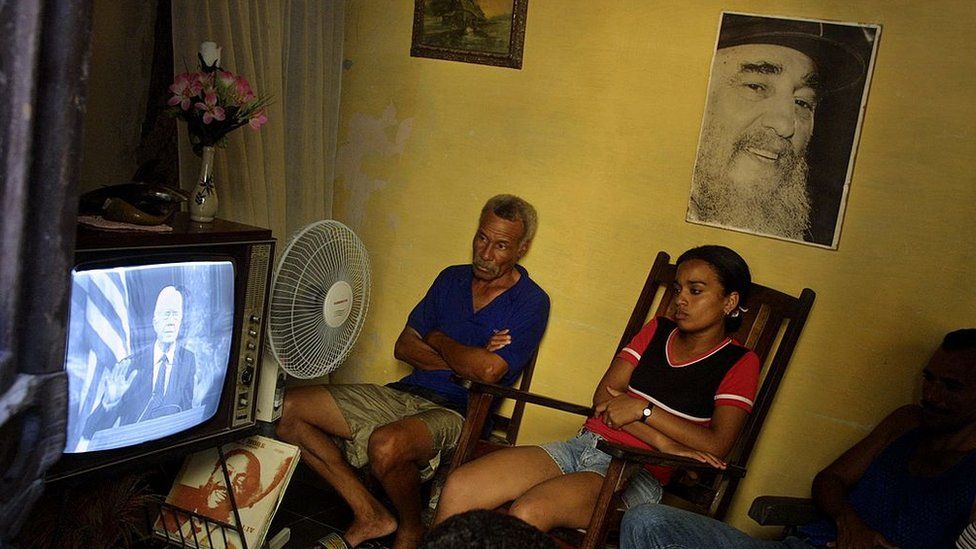

Cuba’s tightly controlled state media had ignored the petition, so many Cubans hadn’t heard of it.

That changed when former US President Jimmy Carter praised the Varela Project, in a speech he gave in Spanish at the University of Havana a few days later – in the presence of none other than Fidel Castro.

As a result, Oswaldo Payá and those who backed the project were catapulted into the forefront of the opposition to the Castro government.

Cuban officials lashed out, accusing the Varela Project of being “financed, encouraged and directed by foreign interests”, while the National Assembly gave no formal response to the petition.

A month later, groups linked to the government called for a referendum of their own to approve an amendment declaring Cuba’s socialist system untouchable.

Fidel Castro led a march of hundreds of thousands of Cubans through the streets of Havana in support of the amendment, in what many saw as an attempt to counter Payá’s calls for more democracy.

The amendment received the backing of 99% of Cuban voters, which was hailed by the government as a sign of the invincibility of the Cuban revolution, but critics said was evidence that most Cubans were too afraid to vote against the government.

A year later, many of the promoters of the Varela Project were imprisoned. Oswaldo Payá was not among them, but denounced being subjected to constant surveillance and harassment by the Cuban authorities.

The extent of these measures against Payá and his family is listed in a report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

It found that Cuban authorities “chased him through the streets in various cars, followed him to church, to work, and agents were stationed at the door of his house”.

Undeterred by these reprisals, Oswaldo Payá carried on his campaign in support of democracy.

On 22 July 2012, he was travelling with Harold Cepero, also from the Varela Project, and two young European politicians – a Spaniard and a Swede – through eastern Cuba when the car they were in crashed.

His daughter, Rosa María, was 23 years old at the time. She recalls how she and her mother received a phone call from supporters of the Varela Project in Europe, who alerted them to the fact that they were getting worrying messages from the two Europeans. “They told us that something had happened to them.”

“I frantically called my dad’s phone and no-one answered, until finally a forensic doctor picked up,” Ms Payá recalls.

“When I shouted at her asking where the owner of the phone was, she at first appeared confused, until she finally told me that there had been a fatality and hung up.”

Oswaldo Payá and Harold Cepero, who had both been sitting in the back of the car, had both died in the crash.

The driver, 26-year-old Spaniard Ángel Carromero, and Swedish youth politician Aron Modig, survived with only minor injuries and were taken to a hospital in the nearby city of Bayamo.

According to the report, the two survivors told friends shortly after the accident that they had been run off the road by another car, which had hit them from behind.

Rosa María Payá says that her family immediately suspected that the crash had been no accident.

They were suspicious because just over a month earlier Oswaldo Payá had survived a similar incident.

Oswaldo Payá and his wife, Ofelia Acevedo, had been driving in the capital Havana, when they were hit by another vehicle from behind with such force that it caused their Volkswagen van to flip over into the opposite lane.

Rosa María Payá told the BBC that she was lucky not to have lost both of her parents that day in June.

According to the report by the IACHR, which has been 10 years in the making, what happened in the aftermath of the crash which killed Payá and Cepero was highly irregular.

The hospital the survivors were taken to was surrounded by soldiers and Mr Carromero told the IACHR that he was “drugged, beaten, and forced to make a false confession by Cuban authorities while in detention that he was at fault for the accident”.

Cuba’s interior ministry created a digital recreation of how it said the accident had unfolded which was shared by state-run media.

It stated that the car had veered off the road and crashed into a tree on a stretch of road which was under repair, full of gravel and therefore “very slippery”. It also quoted three eyewitnesses as saying that the car had been driving “at excessive speed”.

Angelita Baeyens from the advocacy group Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, which brought the case before the IACHR on behalf of the victims’ families, says she has no doubt as to why the Cuban government “pushed the narrative of the accident”.

“They wanted to silence him [Payá] but they could not kill him in a way which would make it too obvious that the state was behind it,” Ms Baeyens, who was the lead lawyer in the case, told the BBC.

The IACHR found many omissions and irregularities in the way Cuban officials investigated the incident. The report says there was an eyewitness who backed up Mr Carromero’s testimony that his car had been hit from behind by an official car, but that witness was neither questioned by police nor called to appear at Mr Carromero’s trial in Cuba.

Mr Carromero was found guilty in October 2012 of manslaughter and sentenced to four years in prison.

In its report, the IACHR concluded that he had been “subjected to an unlawful, arbitrary arrest, threatened by state authorities to get him to confess his alleged responsibility in the crash, and subjected to torture and other forms of inhumane treatment”.

In December 2012, he was transferred to Spain to serve the remainder of his sentence in his home country.

He said that even after his return to Spain, he continued to be threatened.

“I was sent anonymous death threats to my home telling me to keep quiet,” he told the BBC from Madrid.

Mr Carromero described the IACHR report, which identified “serious and sufficient evidence to conclude that state agents participated in the death of Mr Payá and Mr Cepero”, as “coming late, but providing the recognition, so important for the families of Oswaldo [Payá] and Harold [Cepero] and for myself, that what we had been saying all along was true”.

“This report shows that it wasn’t just our truth but the truth.”

The BBC approached the Cuban government with a request for comment on the report, but has not yet received a response.

Cuba did not submit any evidence before the IACHR in relation to this case. In the past, it has denounced the system of regional institutions the IACHR forms part of as “a structure designed by the US to control Latin America”.

Rosa María Payá says she does not expect the Cuban government to take any action in response to the report which she welcomes as “historic” and “a huge relief”.

She is adamant that the Cuban regime “assassinated” her father and that there will only be justice in Cuba once there is freedom and democracy – the very values, she says, her father and Harold Cepero fought for.

Source : BBC